The depth and breadth of the equity and debt capital markets in the United States has been a key driver of the country's economic success. By making capital available to companies of all sizes, from start-ups in Silicon Valley to blue chips on Wall Street, the U.S. system has helped fuel innovation and often given US companies an edge internationally. Through the creation of Rule 506(c) (defined below) and other changes to the rules governing capital raisings in the United States, lawmakers in the United States have sought to open the capital markets even further.

Despite the buoyant markets in the United States, non-U.S. companies are often reluctant to raise funds there due to the relatively litigious nature of U.S. investors, the perceived complications related to the U.S. rules and regulations and the simple fact that reaching investors in the United States can be difficult, particularly for companies that aren't located or very active in the United States.

The new rules around marketing deals implemented following the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (the JOBS Act) and the rise of the utility of the internet, both in marketing and lowering deal costs, could encourage more non-U.S. companies to consider raising funds in the United States.

It's important to note that while crowdfunding (i.e. Title III of the JOBS Act allowing the raising of relatively small amounts of money from a very large number of non-sophisticated investors) gets most of the press, the creation of Rule 506(c) of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the Securities Act) will probably have a much bigger impact for companies raising money from U.S. investors, in part because: (i) Rule 506(c) (and Rule 506(b), for that matter) has no limit on the amount of funds that can be raised, (ii) the risk profile when dealing with the sophisticated investors involved in Rule 506 deals is much lower than will be the case once non-sophisticated investors are able to participate in crowdfunded deals, (iii) the ongoing reporting and regulatory requirements will be lower for Rule 506 deals, both for U.S. and non-U.S. companies (iv) dealing with a limited number of investors is easier for companies of all sizes, and (v) the changes to Rule 506 (i.e. the removal of the general solicitation/advertising ban and the creation of Rule 506(c)) have created to potential to widely advertise and settle deals on the internet.

We have set out below a few of the key considerations in this process and attempted to cut through some of the jargon that often serves as a barrier to raising funds in the United States, both for domestic and non-U.S. companies.

But before any of that, please consult legal counsel before entering this market in any way. The information below is not legal advice, it is only provided as an introduction. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing and if you make a mistake, even if it is inadvertent, there may be serious legal consequences. Go talk to a lawyer.

Foreign Private Issuers and Regulation S

Companies that access the U.S. public or private capital markets (e.g. offer or sell shares to U.S. investors) become subject to federal and state securities laws in the United States. These laws generally apply to U.S. and non-U.S. companies alike. However, sometimes these laws make accommodations for non-U.S. companies. Often these accommodations, which include relaxed reporting and regulatory requirements, make it easier for non-U.S. companies to access the U.S. markets as these exemptions were implemented with the goal of encouraging non-U.S. companies to enter the U.S. capital markets in certain circumstances. Most of the accommodations for non-U.S. companies are available to non-U.S. companies that meet the definition of "foreign private issuer" (FPI).

Definition of FPI

The term "foreign private issuer" means a national of any foreign country or a corporation or other organization incorporated or organized under the laws of any foreign country except an issuer meeting the following conditions:

Although these tests appear straightforward, there are a number of complicating factors. For example, determining who actually holds the issuer's securities for purposes of #1 may involve a "look through analysis" whereby issuers must look through the record ownership to determine whether more than 50% of their voting securities are "beneficially" owned by U.S. residents.

In terms of timing, an issuer is an FPI if it meets the above definition of an FPI on the last business day of its most recently completed second fiscal quarter (though this is different if the issue is registering securities with the SEC for the first time).

It should be noted that although the transaction structures discussed below are available to FPIs and U.S. companies, "non-U.S." companies seeking to raise funds in the United States should be clear on their FPI status before directly subjecting themselves to U.S. (and SEC) jurisdiction by selling securities to U.S. investors. Again, FPI status is important because if such issuers offer and sell securities to investors in the United States, the issuer will be subject to relaxed reporting requirements and will often be able to rely on compliance with its home-country regulations.

Regulation S

Section 5 of the Securities Act prohibits the offer and sale of a security into the United States absent its registration with the SEC, unless both the offer and sale are made in a transaction that is exempt from, or not subject to, such registration requirements.

Although this expressly relates only to offers and sales into the United States, issuers can unintentionally offer securities into the United States and fall foul of the SEC and the registration requirements set out in the Securities Act. It is therefore useful to quickly touch on what comprises an offer that is not subject to the registration requirements because it is made outside of the United States.

Regulation S provides that offers and sales are not subject to Section 5 if they occur outside of the United States (whether or not the buyers are US or foreign investors). There are two basic conditions applicable to any offering by an issuer made pursuant to Regulation S:

"Directed selling efforts" is very broad and includes any activity undertaken for the purpose of, or that could reasonably be expected to have the effect of, conditioning the market in the United States for the securities being offered offshore. This could include nearly any activity that results in information about a fundraising reaching investors in the United States (including over the internet) or even activity that raises the issuers profile in the United States at a time when it is raising funds with non-U.S. investors.

Most non-U.S. companies don't worry about their FPI status or making sure they fall within Regulation S, particularly if they haven't had and don't plan on having contact with U.S. investors. These issuers almost certainly fall within Regulation S, even if they don't know it. But things can get complicated and it's an important analysis for companies considering interaction with investors in the United States to stay within Regulation S, if necessary.

Private Fundraisings in the United States

Issuer Private Placements pursuant to Section 4(a)(2) and Regulation D

As noted above, Section 5 of the Securities Act prohibits the offer and sale of a security into the United States absent its registration with the SEC, unless both the offer and sale are made in a transaction that is exempt from, or not subject to, such registration requirements. Relatively few FPIs attempt to register their offerings with the SEC; the preferred alternative being to utilize private placement exemptions, the most commonly used being:

Section 4(a)(2)

Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act exempts from registration offers and sales by the issuer that do not involve a public offering or distribution (hence, ‘private placement’). While the term public offering has never been defined formally by the SEC, several factors have emerged from case law and SEC rulings that set out when transactions are not deemed to involve a public offering for purposes of Section 4(a)(2):

Regulation D (Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c))

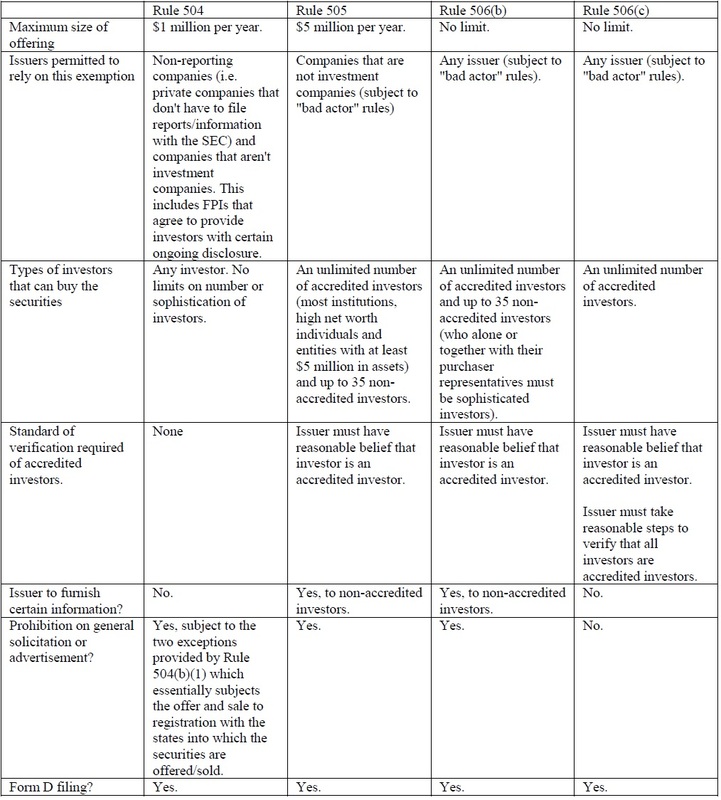

Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) of Regulation D are private placement exemptions that provide a few different options for issuers seeking to raise capital from U.S. investors. Each exemption contains certain requirements and limitations that may make them more or less attractive depending on the potential deal size, the issuer and the potential investor base.

Prior to the JOBS Act and the creation of Rule 506(c), offers of securities to U.S. investors pursuant to any rule under Regulation D could not be made by means of any form of "general solicitation" or "general advertising". As noted above, these terms include a very wide range of marketing activities and would likely include posting the offer of securities on a website which is available to the public or which does not have active screening or investor verification procedures, as discussed below. As a result, marketing activities in the United States in relation to private placements pursuant to Rules 504 through Rule 506 typically have been directed at a restricted number of sophisticated investors.

Although Rule 504, Rule 505 and Rule 506(b) still prohibit general solicitation and general advertising, issuers may publicize their offers more widely if they are making an offer pursuant to Rule 506(c). This has the potential to open up the internet to so called "private placements" by issuers, both U.S. issuers and FPIs, subject to the other restrictions set out in Rule 506(c) discussed below.

The Differences between Rules 504, 505, 506(b) and 506(c)

Prior to the creation of Rule 506(c), the fundamental differences between Rules 504 through 506 were the amount of money that could be raised and the type of investors that could be targeted. Rule 504 caps the total amount that can be raised at $1 million per year and does not limit the number of investors or the sophistication of those investors. On the other end of the spectrum, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) have no limit to the amount of money that can be raised, though Rule 506(b) only allows for 35 non-accredited investors and Rule 506(c) allows for zero non-accredited investors.

Note again that each exemption in Regulation D, except for Rule 506(c) effectively prohibits general solicitation and general advertising. Although Rule 504 includes exceptions to this prohibition, issuers that avail themselves of these exceptions must register the securities in at least one state. On a related point, note that securities offered and sold pursuant to Rule 506 are considered to be "covered securities", while securities issued pursuant to Rules 504 and 505 are not. U.S. state securities laws (or "Blue Sky Laws") apply to the offer of sale of securities to investors in the relevant state, unless the securities are "covered securities" and therefore exempted by federal securities laws. Blue Sky Laws can be very different from state to state and compliance with these laws can be expensive and complicated.

The table below sets out some of the basic information for Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c):

The new rules around marketing deals implemented following the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (the JOBS Act) and the rise of the utility of the internet, both in marketing and lowering deal costs, could encourage more non-U.S. companies to consider raising funds in the United States.

It's important to note that while crowdfunding (i.e. Title III of the JOBS Act allowing the raising of relatively small amounts of money from a very large number of non-sophisticated investors) gets most of the press, the creation of Rule 506(c) of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the Securities Act) will probably have a much bigger impact for companies raising money from U.S. investors, in part because: (i) Rule 506(c) (and Rule 506(b), for that matter) has no limit on the amount of funds that can be raised, (ii) the risk profile when dealing with the sophisticated investors involved in Rule 506 deals is much lower than will be the case once non-sophisticated investors are able to participate in crowdfunded deals, (iii) the ongoing reporting and regulatory requirements will be lower for Rule 506 deals, both for U.S. and non-U.S. companies (iv) dealing with a limited number of investors is easier for companies of all sizes, and (v) the changes to Rule 506 (i.e. the removal of the general solicitation/advertising ban and the creation of Rule 506(c)) have created to potential to widely advertise and settle deals on the internet.

We have set out below a few of the key considerations in this process and attempted to cut through some of the jargon that often serves as a barrier to raising funds in the United States, both for domestic and non-U.S. companies.

But before any of that, please consult legal counsel before entering this market in any way. The information below is not legal advice, it is only provided as an introduction. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing and if you make a mistake, even if it is inadvertent, there may be serious legal consequences. Go talk to a lawyer.

Foreign Private Issuers and Regulation S

Companies that access the U.S. public or private capital markets (e.g. offer or sell shares to U.S. investors) become subject to federal and state securities laws in the United States. These laws generally apply to U.S. and non-U.S. companies alike. However, sometimes these laws make accommodations for non-U.S. companies. Often these accommodations, which include relaxed reporting and regulatory requirements, make it easier for non-U.S. companies to access the U.S. markets as these exemptions were implemented with the goal of encouraging non-U.S. companies to enter the U.S. capital markets in certain circumstances. Most of the accommodations for non-U.S. companies are available to non-U.S. companies that meet the definition of "foreign private issuer" (FPI).

Definition of FPI

The term "foreign private issuer" means a national of any foreign country or a corporation or other organization incorporated or organized under the laws of any foreign country except an issuer meeting the following conditions:

- More than 50% of the issuer's outstanding voting securities are directly or indirectly held of record by U.S. residents; and

- Any one of the following:

- the majority of the executive officers or directors are U.S. citizens or residents;

- more than 50% of the issuer's assets are located in the United States; or

- the issuer's business is administered principally in the United States.

Although these tests appear straightforward, there are a number of complicating factors. For example, determining who actually holds the issuer's securities for purposes of #1 may involve a "look through analysis" whereby issuers must look through the record ownership to determine whether more than 50% of their voting securities are "beneficially" owned by U.S. residents.

In terms of timing, an issuer is an FPI if it meets the above definition of an FPI on the last business day of its most recently completed second fiscal quarter (though this is different if the issue is registering securities with the SEC for the first time).

It should be noted that although the transaction structures discussed below are available to FPIs and U.S. companies, "non-U.S." companies seeking to raise funds in the United States should be clear on their FPI status before directly subjecting themselves to U.S. (and SEC) jurisdiction by selling securities to U.S. investors. Again, FPI status is important because if such issuers offer and sell securities to investors in the United States, the issuer will be subject to relaxed reporting requirements and will often be able to rely on compliance with its home-country regulations.

Regulation S

Section 5 of the Securities Act prohibits the offer and sale of a security into the United States absent its registration with the SEC, unless both the offer and sale are made in a transaction that is exempt from, or not subject to, such registration requirements.

Although this expressly relates only to offers and sales into the United States, issuers can unintentionally offer securities into the United States and fall foul of the SEC and the registration requirements set out in the Securities Act. It is therefore useful to quickly touch on what comprises an offer that is not subject to the registration requirements because it is made outside of the United States.

Regulation S provides that offers and sales are not subject to Section 5 if they occur outside of the United States (whether or not the buyers are US or foreign investors). There are two basic conditions applicable to any offering by an issuer made pursuant to Regulation S:

- The offer and sale of the securities must be made in an "offshore transaction".

- There can be no "directed selling efforts" in or into the United States of the securities offered.

"Directed selling efforts" is very broad and includes any activity undertaken for the purpose of, or that could reasonably be expected to have the effect of, conditioning the market in the United States for the securities being offered offshore. This could include nearly any activity that results in information about a fundraising reaching investors in the United States (including over the internet) or even activity that raises the issuers profile in the United States at a time when it is raising funds with non-U.S. investors.

Most non-U.S. companies don't worry about their FPI status or making sure they fall within Regulation S, particularly if they haven't had and don't plan on having contact with U.S. investors. These issuers almost certainly fall within Regulation S, even if they don't know it. But things can get complicated and it's an important analysis for companies considering interaction with investors in the United States to stay within Regulation S, if necessary.

Private Fundraisings in the United States

Issuer Private Placements pursuant to Section 4(a)(2) and Regulation D

As noted above, Section 5 of the Securities Act prohibits the offer and sale of a security into the United States absent its registration with the SEC, unless both the offer and sale are made in a transaction that is exempt from, or not subject to, such registration requirements. Relatively few FPIs attempt to register their offerings with the SEC; the preferred alternative being to utilize private placement exemptions, the most commonly used being:

- Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act (formerly Section 4(2) before its re-designation by the JOBS Act); and

- Regulation D, which supplements Section 4(a)(2) by setting out specific requirements for how to conduct private placements.

Section 4(a)(2)

Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act exempts from registration offers and sales by the issuer that do not involve a public offering or distribution (hence, ‘private placement’). While the term public offering has never been defined formally by the SEC, several factors have emerged from case law and SEC rulings that set out when transactions are not deemed to involve a public offering for purposes of Section 4(a)(2):

- Sophistication of the investors: Offerees must be sophisticated and have knowledge and experience of financial and business matters to evaluate the risks and merits of offerings that are not subject to the same process as deals that are registered with the SEC. Sophisticated investors would include "accredited investors" and "qualified institutional buyers" (as defined in Rule 501 and Rule 144A, respectively).

- Limited number of investors. Although there is no express requirement to limit the number of investors, issuers generally try to control the number of offerees and investors in order to avoid selling to unsophisticated investor or raise the potential violation of the following restriction.

- Prohibition on general solicitation and general advertising. Neither the issuer (nor anyone acting on its behalf) can offer or sell securities by means of any form of "general solicitation" or "general advertising". General solicitation and general advertising is very broad and would likely include posting information on a website. As discussed below, the JOBS Act did not amend this prohibition as it relates to Section 4(a)(2).

- Information requirement. Although Section 4(a)(2) does not require any specific information to be furnished to investors, potential investors may receive a private placement memorandum, which is a disclosure document prepared by the issuer that provides investors with basic information about the issuer and the securities being offered.

- Transfer restrictions on restricted securities. Buyers are generally required to buy larger blocks of unregistered securities that carry transfer restrictions to increase the likelihood these restricted securities are bought by suitably sophisticated investors.

- Investment intent. Investors must buy the unregistered securities for their own account, without a view to resell or distribute them to others immediately.]

Regulation D (Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c))

Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) of Regulation D are private placement exemptions that provide a few different options for issuers seeking to raise capital from U.S. investors. Each exemption contains certain requirements and limitations that may make them more or less attractive depending on the potential deal size, the issuer and the potential investor base.

Prior to the JOBS Act and the creation of Rule 506(c), offers of securities to U.S. investors pursuant to any rule under Regulation D could not be made by means of any form of "general solicitation" or "general advertising". As noted above, these terms include a very wide range of marketing activities and would likely include posting the offer of securities on a website which is available to the public or which does not have active screening or investor verification procedures, as discussed below. As a result, marketing activities in the United States in relation to private placements pursuant to Rules 504 through Rule 506 typically have been directed at a restricted number of sophisticated investors.

Although Rule 504, Rule 505 and Rule 506(b) still prohibit general solicitation and general advertising, issuers may publicize their offers more widely if they are making an offer pursuant to Rule 506(c). This has the potential to open up the internet to so called "private placements" by issuers, both U.S. issuers and FPIs, subject to the other restrictions set out in Rule 506(c) discussed below.

The Differences between Rules 504, 505, 506(b) and 506(c)

Prior to the creation of Rule 506(c), the fundamental differences between Rules 504 through 506 were the amount of money that could be raised and the type of investors that could be targeted. Rule 504 caps the total amount that can be raised at $1 million per year and does not limit the number of investors or the sophistication of those investors. On the other end of the spectrum, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) have no limit to the amount of money that can be raised, though Rule 506(b) only allows for 35 non-accredited investors and Rule 506(c) allows for zero non-accredited investors.

Note again that each exemption in Regulation D, except for Rule 506(c) effectively prohibits general solicitation and general advertising. Although Rule 504 includes exceptions to this prohibition, issuers that avail themselves of these exceptions must register the securities in at least one state. On a related point, note that securities offered and sold pursuant to Rule 506 are considered to be "covered securities", while securities issued pursuant to Rules 504 and 505 are not. U.S. state securities laws (or "Blue Sky Laws") apply to the offer of sale of securities to investors in the relevant state, unless the securities are "covered securities" and therefore exempted by federal securities laws. Blue Sky Laws can be very different from state to state and compliance with these laws can be expensive and complicated.

The table below sets out some of the basic information for Rule 504, Rule 505, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c):

Rule 504, Rule 505 and Rule 506(b) are each complicated, but we will not discuss them much further here. Rule 506(b), in particular, can be very useful to FPIs and will be touched on a bit below. The focus will be Rule 506(c), however, as this rule is new to the market and may represent a real opportunity for FPIs.

Verification of Investor Status under Rule 506(c)

Rule 506(c) allows a company to generally advertise an offering of securities in the United States (including on the internet), provided that all investors are "accredited investors" and the company takes reasonable steps to verify that the investors are accredited investors.

The SEC release provides that the determination of whether the steps taken to verify accredited investor status are "reasonable" is "an objective determination by the issuer (or those acting on its behalf), in the context of the particular facts and circumstances of each purchaser and transaction". The SEC proposed a number of factors that might be considered in this "principles-based approach":

· the nature of the purchaser and the type of accredited investor that the purchaser claims to be;

· the amount and type of information that the issuer has about the purchaser; and

· the nature of the offering, such as the manner in which the purchaser was solicited to participate in the offering, and the terms of the offering, such as a minimum investment amount.

The SEC also stated that "[t]hese factors would be interconnected, and the information gained by looking at these factors would help an issuer assess the reasonable likelihood that a potential purchaser is an accredited investor, which would, in turn, affect the types of steps that would be reasonable to take to verify a purchaser’s accredited investor status."

Furthermore, the SEC recognizes that although verification of the status and sophistication of institutional investors may be relatively easy, verification may be more difficult if the investor is a natural person.

Rule 506(c) therefore also sets out a non-exclusive list of methods that companies (or third parties) may use to satisfy the verification requirement for investors who are natural persons:

· receipt of certain documentation of levels of income or net worth of the purchaser (such as tax returns, bank statements, and credit reports);

· verification of accredited investor status from certain third-parties, such as a registered broker-dealer, a registered investment adviser, a licensed attorney, or a certified public accountant; or

· for an existing shareholder which previously purchased in a Rule 506 offering by the company, the receipt of a certification from the purchaser that it still meets the definition of an accredited investor

If the investor's status is to be established by verification of his or her net worth as per the first method above, the release states that the verification requirement will be met if the noted documentation is reviewed and the investor provides "a written representation that all liabilities necessary to make a determination of net worth have been disclosed".

Note that the requirement to take reasonable steps to verify that all purchasers are accredited investors is independent of the requirement that sales be made solely to accredited investors, and must be satisfied even if all purchasers happen to be accredited investors. The release states that it will be important for issuers (and any third party verification service providers) "to retain records regarding the steps taken to verify that a purchaser was an accredited investor".

The SEC has left the previous formulation of Rule 506 unchanged in the form of Rule 506(b). Although issuers must still reasonably believe that investors are accredited investors, issuers will not be subject to the verification or related record retention requirements if they do not employ general solicitation or general advertising in reliance upon Rule 506(c). Note also that issuers conducting offerings pursuant to Rule 506(b) may still offer and sell securities to no more than 35 sophisticated non-accredited investors, which is not the case for issuers pursuing Rule 506(c) offerings.

Impact of Rule 506(c) on the private placement market for U.S. issuers and FPIs.

So what does the creation of Rule 506(c) mean for companies (both U.S. issuers and FPIs) looking to raise cash? The short answer is that these changes will likely have a major impact on the way that companies raise money from sophisticated investors in what now seems to be ‘semi-private’ offerings. True equity "crowdfunding" is not impacted by these new rules. The rules governing that market are yet to come.

It is likely that we will continue to see more angel networks, venture capital groups and securities brokers bring companies and accredited investors together online. These offerings and platforms will likely have some or all of the following characteristics:

· access to the site may be available to accredited and non-accredited investors (though issuers may be able to pursue Rule 506(b) if only accredited investors were given access to the site);

· the ability to invest will be granted to accredited investors only;

· verification of the investor's status will be completed by a variety of methods, including representations from the investor and the provision of certain information to the company (or platform, broker, etc) by the investor that proves the investor's status;

· verification may be completed by third party service providers;

· records will be kept by the party that verifies the investor's status; and

· Form D will be filed by the company, the broker or perhaps through the platform.

"Global" Fundraisings

So what are the options for FPIs?

Let's take a hypothetical company, Acme plc. Its shares are all owned by its founders (members of its board or employees (both current and former) that are spread out around Europe), its operations are conducted almost entirely outside of the United States (except for a small proportion of sales), its assets consist almost entirely of IP and IT held in Europe and its board of directors are all European citizens living in the United Kingdom. Therefore, subject to confirming with their lawyers, Acme plc appears to be an FPI.

Acme plc would like to raise £5 million in order to build its mobile site and increase its marketing spend. It was able to raise the first £3 million relatively easily from members of its board and other friendly investors in the United Kingdom procured by U.K. Fake Financial Capital (a financial adviser), but the last £2 million proved to be more difficult.

U.K. Fake Financial Capital has a relationship with a U.S. financial adviser (U.S. Fake Advisor) that is registered as a broker dealer with the SEC and, given Acme's primary markets and the activity of U.S. investors in these segments, U.K. Fake Financial Capital suggests that it may be able to find investors in the United States to round out Acme’s fundraise.

U.S. Fake Advisor has recently set up a new website/platform in order to advertise and facilitate fundraisings. Although the deals on the platform can be viewed by anyone, only accredited investors (that are verified by U.S. Fake Advisor or by a third party service provider) may invest.

Acme plc contacts U.S. Fake Advisor and, after the necessary diligence and paperwork, engages U.S. Fake Advisor to assist the company in finding U.S. accredited investors for its fundraising. A few weeks after posting the details of the fundraising on the website, communicating with interested investors and responding to their questions, Acme plc has raised $3.5 million needed to close out its fundraising.

So, in this perhaps overly rosy scenario, what do we have?

Although there are many details and more than a few steps left out of the discussion above, we have the makings of an offer and sale of securities to investors in the United Kingdom pursuant to Regulation S and an offer and sale of securities to accredited investors in the United States presumably pursuant to Rule 506(c). Note that if U.S. Fake Advisor had determined that it would simply contact a few accredited investors the old-fashioned way (i.e. by telephone or even email) or by providing only verified accredited investors with access to the platform (instead of posting the offer to a platform/website that was open to the public), the offer may have been made pursuant to Rule 506(b).

Takeaways for FPIs

There are a few basic steps or principals that FPIs need to keep in mind if they are considering raising money in the United States:

Conclusion

The creation of a crowdfunding market and the liberalisation of the advertising and marketing restrictions for private offerings set out in the JOBS Act clearly represent significant changes to the U.S. capital markets. Crowdfunding may develop into yet another option for companies seeking to raise capital in the United States and the lifting of the ban on general solicitation and advertising will likely make this already enormous market more efficient and user-friendly by bringing it online.

Regardless of these changes, however, raising capital in the United States will remain a relatively complicated process that involves risk for issuers and other transaction participants. This is unavoidable as the SEC, FINRA and the courts (not to mention the lawyers) are all active watchdogs.

Unfortunately, these risks are often misunderstood, particularly by non-U.S. companies. With proper advice, thousands of non-U.S. companies tap the U.S. capital markets every year and the changes resulting from the JOBS Act that will drive the ability of U.S. companies to raise funds can do the same for non-U.S. companies.

Image Credit to: Manu_H. http://bit.ly/1fZyrlJ

Verification of Investor Status under Rule 506(c)

Rule 506(c) allows a company to generally advertise an offering of securities in the United States (including on the internet), provided that all investors are "accredited investors" and the company takes reasonable steps to verify that the investors are accredited investors.

The SEC release provides that the determination of whether the steps taken to verify accredited investor status are "reasonable" is "an objective determination by the issuer (or those acting on its behalf), in the context of the particular facts and circumstances of each purchaser and transaction". The SEC proposed a number of factors that might be considered in this "principles-based approach":

· the nature of the purchaser and the type of accredited investor that the purchaser claims to be;

· the amount and type of information that the issuer has about the purchaser; and

· the nature of the offering, such as the manner in which the purchaser was solicited to participate in the offering, and the terms of the offering, such as a minimum investment amount.

The SEC also stated that "[t]hese factors would be interconnected, and the information gained by looking at these factors would help an issuer assess the reasonable likelihood that a potential purchaser is an accredited investor, which would, in turn, affect the types of steps that would be reasonable to take to verify a purchaser’s accredited investor status."

Furthermore, the SEC recognizes that although verification of the status and sophistication of institutional investors may be relatively easy, verification may be more difficult if the investor is a natural person.

Rule 506(c) therefore also sets out a non-exclusive list of methods that companies (or third parties) may use to satisfy the verification requirement for investors who are natural persons:

· receipt of certain documentation of levels of income or net worth of the purchaser (such as tax returns, bank statements, and credit reports);

· verification of accredited investor status from certain third-parties, such as a registered broker-dealer, a registered investment adviser, a licensed attorney, or a certified public accountant; or

· for an existing shareholder which previously purchased in a Rule 506 offering by the company, the receipt of a certification from the purchaser that it still meets the definition of an accredited investor

If the investor's status is to be established by verification of his or her net worth as per the first method above, the release states that the verification requirement will be met if the noted documentation is reviewed and the investor provides "a written representation that all liabilities necessary to make a determination of net worth have been disclosed".

Note that the requirement to take reasonable steps to verify that all purchasers are accredited investors is independent of the requirement that sales be made solely to accredited investors, and must be satisfied even if all purchasers happen to be accredited investors. The release states that it will be important for issuers (and any third party verification service providers) "to retain records regarding the steps taken to verify that a purchaser was an accredited investor".

The SEC has left the previous formulation of Rule 506 unchanged in the form of Rule 506(b). Although issuers must still reasonably believe that investors are accredited investors, issuers will not be subject to the verification or related record retention requirements if they do not employ general solicitation or general advertising in reliance upon Rule 506(c). Note also that issuers conducting offerings pursuant to Rule 506(b) may still offer and sell securities to no more than 35 sophisticated non-accredited investors, which is not the case for issuers pursuing Rule 506(c) offerings.

Impact of Rule 506(c) on the private placement market for U.S. issuers and FPIs.

So what does the creation of Rule 506(c) mean for companies (both U.S. issuers and FPIs) looking to raise cash? The short answer is that these changes will likely have a major impact on the way that companies raise money from sophisticated investors in what now seems to be ‘semi-private’ offerings. True equity "crowdfunding" is not impacted by these new rules. The rules governing that market are yet to come.

It is likely that we will continue to see more angel networks, venture capital groups and securities brokers bring companies and accredited investors together online. These offerings and platforms will likely have some or all of the following characteristics:

· access to the site may be available to accredited and non-accredited investors (though issuers may be able to pursue Rule 506(b) if only accredited investors were given access to the site);

· the ability to invest will be granted to accredited investors only;

· verification of the investor's status will be completed by a variety of methods, including representations from the investor and the provision of certain information to the company (or platform, broker, etc) by the investor that proves the investor's status;

· verification may be completed by third party service providers;

· records will be kept by the party that verifies the investor's status; and

· Form D will be filed by the company, the broker or perhaps through the platform.

"Global" Fundraisings

So what are the options for FPIs?

Let's take a hypothetical company, Acme plc. Its shares are all owned by its founders (members of its board or employees (both current and former) that are spread out around Europe), its operations are conducted almost entirely outside of the United States (except for a small proportion of sales), its assets consist almost entirely of IP and IT held in Europe and its board of directors are all European citizens living in the United Kingdom. Therefore, subject to confirming with their lawyers, Acme plc appears to be an FPI.

Acme plc would like to raise £5 million in order to build its mobile site and increase its marketing spend. It was able to raise the first £3 million relatively easily from members of its board and other friendly investors in the United Kingdom procured by U.K. Fake Financial Capital (a financial adviser), but the last £2 million proved to be more difficult.

U.K. Fake Financial Capital has a relationship with a U.S. financial adviser (U.S. Fake Advisor) that is registered as a broker dealer with the SEC and, given Acme's primary markets and the activity of U.S. investors in these segments, U.K. Fake Financial Capital suggests that it may be able to find investors in the United States to round out Acme’s fundraise.

U.S. Fake Advisor has recently set up a new website/platform in order to advertise and facilitate fundraisings. Although the deals on the platform can be viewed by anyone, only accredited investors (that are verified by U.S. Fake Advisor or by a third party service provider) may invest.

Acme plc contacts U.S. Fake Advisor and, after the necessary diligence and paperwork, engages U.S. Fake Advisor to assist the company in finding U.S. accredited investors for its fundraising. A few weeks after posting the details of the fundraising on the website, communicating with interested investors and responding to their questions, Acme plc has raised $3.5 million needed to close out its fundraising.

So, in this perhaps overly rosy scenario, what do we have?

Although there are many details and more than a few steps left out of the discussion above, we have the makings of an offer and sale of securities to investors in the United Kingdom pursuant to Regulation S and an offer and sale of securities to accredited investors in the United States presumably pursuant to Rule 506(c). Note that if U.S. Fake Advisor had determined that it would simply contact a few accredited investors the old-fashioned way (i.e. by telephone or even email) or by providing only verified accredited investors with access to the platform (instead of posting the offer to a platform/website that was open to the public), the offer may have been made pursuant to Rule 506(b).

Takeaways for FPIs

There are a few basic steps or principals that FPIs need to keep in mind if they are considering raising money in the United States:

- It's possible to raise a portion of your fund outside of the United States and a portion inside the United States.

- Assessing and maintaining your status as a FPI will minimize your ongoing reporting and other requirements if you do raise money in the United States.

- Offers and sales of securities in the United States must either be registered or made pursuant to an exemption.

- Although each case is different, offers and sales to accredited investors generally carry less risk than offers and sales to non-accredited investors.

- One of the many issues that wasn't covered in this note is that the FPI will almost certainly need the help of a U.S. registered broker dealer. The rules covering broker dealers (which can include a company selling its own shares and employees of the company doing so) are very complicated and are often a particular point of emphasis for the SEC. Beware. Talk to a lawyer and know that working with a registered broker dealer is highly likely.

Conclusion

The creation of a crowdfunding market and the liberalisation of the advertising and marketing restrictions for private offerings set out in the JOBS Act clearly represent significant changes to the U.S. capital markets. Crowdfunding may develop into yet another option for companies seeking to raise capital in the United States and the lifting of the ban on general solicitation and advertising will likely make this already enormous market more efficient and user-friendly by bringing it online.

Regardless of these changes, however, raising capital in the United States will remain a relatively complicated process that involves risk for issuers and other transaction participants. This is unavoidable as the SEC, FINRA and the courts (not to mention the lawyers) are all active watchdogs.

Unfortunately, these risks are often misunderstood, particularly by non-U.S. companies. With proper advice, thousands of non-U.S. companies tap the U.S. capital markets every year and the changes resulting from the JOBS Act that will drive the ability of U.S. companies to raise funds can do the same for non-U.S. companies.

Image Credit to: Manu_H. http://bit.ly/1fZyrlJ

About the author - Dan McNamee

Dan is a U.S. trained and qualified lawyer (New York) with extensive experience in capital markets and M&A transactions in the United States, Europe, Asia and Africa. This background has provided extensive exposure to rules, regulations and regulators (including the SEC and FINRA) governing many forms of capital raising in the United States. With this foundation in the traditional capital markets space, Dan is seeking to help grow the crowdfunding market in the United States in a manner that encourages capital formation, protects investors and meets the extensive requirements of the nation’s regulators.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Dan has worked and lived throughout the United States, in London and elsewhere in Europe. In his spare time, Dan has contributed a significant amount of pro bono work to a number of organizations, including the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and enjoys suffering as he watches Cleveland’s consistently terrible sports teams lose.

Dan is a U.S. trained and qualified lawyer (New York) with extensive experience in capital markets and M&A transactions in the United States, Europe, Asia and Africa. This background has provided extensive exposure to rules, regulations and regulators (including the SEC and FINRA) governing many forms of capital raising in the United States. With this foundation in the traditional capital markets space, Dan is seeking to help grow the crowdfunding market in the United States in a manner that encourages capital formation, protects investors and meets the extensive requirements of the nation’s regulators.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Dan has worked and lived throughout the United States, in London and elsewhere in Europe. In his spare time, Dan has contributed a significant amount of pro bono work to a number of organizations, including the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and enjoys suffering as he watches Cleveland’s consistently terrible sports teams lose.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed